How World War II reshaped science in Germany and why it still matters today

new

How World War II Reshaped German Science – And Why It Still Matters Today

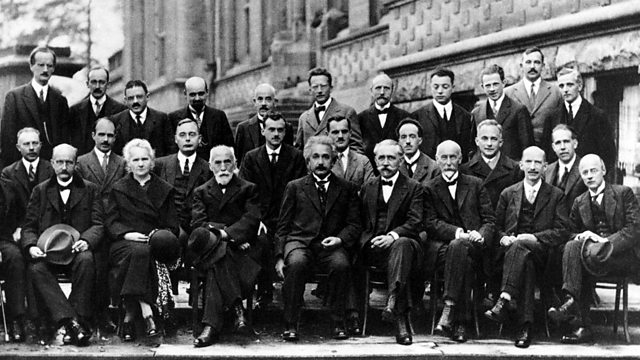

Before the Second World War, Germany was the beating heart of global science. Its universities and research institutes set the standards in physics, chemistry, and mathematics. Many of the names that fill modern textbooks—Einstein, Planck, Born, Heisenberg—were trained or active in the German-speaking academic world. This dominance did not simply fade because other countries “caught up.” It was actively dismantled by political choices, war, and the way the post-war world handled German knowledge and talent.

In this post, I want to look at what happened to German science during the Second World War and how those events still shape both the scientific and economic landscape we see today.

1. From world leader to self-sabotage

The crisis of German science began even before tanks started moving. In 1933, the Nazi regime introduced laws that pushed Jewish academics and politically “unreliable” scholars out of universities and research institutes. This hit theoretical physics and chemistry especially hard, precisely the fields in which Germany had been strongest. Some scientists were dismissed outright; others left because they understood very well what this new political climate meant for their future.

The result was a dramatic intellectual emigration. Many of the most creative minds moved to the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and other countries. They did not only save themselves. They also carried with them Germany’s scientific tradition, methods, and style of thinking. By the time the war truly began, Germany had already damaged its own position. The country that had been at the center of modern physics had deliberately pushed away a large part of its own elite. The war then amplified and hardened this trend.

2. Science under the shadow of war

During the war, science in Germany did not disappear. In some areas it was even heavily funded, but in a one-sided, militarized way. The regime invested strongly in fields that promised immediate military advantage: rocket technology, aeronautics, jet engines, synthetic fuels, and certain areas of nuclear and radar research. Scientists who were considered politically reliable and willing to work for these goals often had access to resources that were denied to other areas of research.

This focus came at a price. Fundamental, curiosity-driven research and the open exchange of ideas, which are crucial for long-term scientific progress, were pushed aside. Laboratories and universities were increasingly reorganised around military priorities. At the same time, the physical infrastructure of science, buildings, libraries, equipment was damaged or destroyed by bombing. International collaboration almost completely collapsed. Conferences could not be held, travel was restricted, and scientific journals became harder to access or publish in.

So even where wartime German science achieved impressive technical results, it did so in a narrow corridor defined by war aims. Instead of a broad, vibrant scientific ecosystem, Germany ended up with islands of advanced technology floating in an environment that was intellectually and morally poisoned.

3. The second wave of loss: brains as war reparations

When the war ended, one might imagine that German science could simply rebuild itself around those who had stayed. In reality, a second major wave of intellectual loss began. The victorious powers quickly understood how advanced some German technologies were, from rockets to aerodynamics to chemical processes, and they treated scientific expertise as a kind of war prize.

The United States, for example, organized programs to bring German scientists and engineers across the Atlantic. Many rocket specialists, including Wernher von Braun and his team, ended up working for the US military and later for NASA. Their knowledge, developed in wartime Germany, helped shape the American space program and missile technology. Similar efforts took place in the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, where specialists were relocated, sometimes along with their families, and integrated into national research projects.

At the same time, patents, industrial processes, and technical documents were collected, copied, or confiscated. Knowledge that could have served as the foundation for a renewed German high-tech economy was now feeding innovation elsewhere. Germany did not only lose factories and buildings. It lost the human capital and intellectual property that had been at the core of its pre-war scientific and economic strength.

4. From unique superpower to one strong player among many

Today, Germany is still a strong scientific nation. It has excellent universities, influential research organizations, and a significant research budget. But it no longer occupies the almost unique position it held in the early twentieth century. Understanding why means looking at both the direct and indirect consequences of the war.

First, the scientists who left between 1933 and 1945 mostly did not come back. They built new schools and traditions in their host countries, trained generations of students, and helped create new centers of excellence abroad. The intellectual networks that once had their natural center in Berlin, Göttingen, or Munich shifted to places like Princeton, Chicago, Cambridge (US and UK), and later to many other cities around the world.

Second, the reconstruction of German science after 1945 took time and happened under difficult conditions. The country was divided into occupation zones and later into East and West, each with its own political system and priorities. New research structures had to be set up or rebuilt, sometimes in the shadow of heavy distrust from the international community. During those crucial decades, the United States and other countries were investing massively in research, especially in the context of the Cold War, and were attracting talent from all over the world.

Third, the division of Germany into East and West meant that scientific resources, people, and institutions were split for decades. While both sides built respectable scientific systems, the fragmentation reduced the overall impact compared to the unified pre 1933 academic landscape. Only after reunification in 1990 did it become possible to think again in terms of a single German science system but by then the global map of science had long since become multicentered.

5. Echoes in today’s scientific and economic landscape

The consequences of these historical processes are still visible. Many of the big research traditions that could have remained firmly anchored in Germany are now distributed across several countries. The American dominance in certain areas of physics and engineering, for example, is directly linked to the emigration and recruitment of European, especially German-speaking, scientists in the 1930s and 1940s.

Within Germany, the modern structure of research with organizations such as the Max Planck Society, the Fraunhofer institutes, and other large research centers can be seen as a deliberate attempt to build something stable and resilient after the collapse caused by dictatorship and war. The system is strong and productive, but it is no longer operating from a position of near-monopoly in key fields. Instead, Germany is one powerful node in a dense global network.

When people say that “Germany is not as strong anymore” in science, this can be misleading. The country remains highly competitive and innovative. What has changed is the historical context. Before 1933, Germany’s dominance was extraordinary. The combination of political persecution, wartime destruction, post-war exploitation of knowledge, and the global reorientation of talent ended that exceptional position. The damage was not only moral and human; it also reshaped the world’s scientific and economic balance.

For scientists working in Germany today, this history is more than a distant story. It is a reminder that scientific strength depends not only on brilliant individuals, but also on political freedom, stable institutions, and the ability to attract and keep talent. The Second World War showed how quickly a leading scientific culture can be undermined and how long its consequences can echo through the laboratories, universities, and economies of the twenty-first century.